Overview

The portable executable file format is a type of format used in 32 and 64bit Windows operating systems and includes items such as object code, DLLs font files and core dumps embedded within in order to execute on a host system. Understanding the PE file format is important when reverse engineering or performing malware analysis on a suspicious executable file, particularly during the manual analysis of a file via a decompiler or debugger.

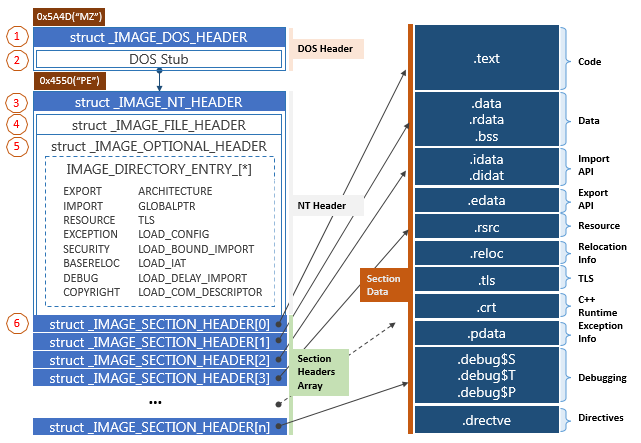

PE File Header

Executable files follow a standardized structure called the Common Object File Format (COFF), PE Files are a COFF formatted executable used within Windows Operating Systems, encapsulating formats such as Executable (.exe, .cpl, .sys, etc), object code and DLLs. The PE file format contains integral information required by the Windows OS to efficiently load and execute the file. Understanding the different components of a PE file is fundamental to performing malware analysis.

The PE file format contains a data structure that allows the Operating System to identify the required components required to execute the file, including such information as metadata covering file type, import and export functions, memory addresses and others.

The sections area of the PE format contains several components of which are Important to understand for malware analysis, with the mostly commonly encountered being:

- .text: Contains the executable component of the program that the operating system will execute. This should be the only section with execute privileges and to contain resident code.

- .rdata: Contains the import and export information. It can also be used to store other read-only data used by the program. Import and export sections can be subdivided into .idata and .edata respectively.

- .data: Contains the global data required by the program.

- .rsrc: Contains the resources used by the application such as icons, images, menus and strings.

Each of the sections above have their own header in which section sizes, both on disk and virtual, are listed. Typically, the size should be relatively close when investigating files, an exception is the .data section which commonly has a larger mismatch in size variables. Size discrepancies can be indicative of packed software as the packing/unpacking code will be loaded in memory.

The .rsrc section can at time bear fruitful information. Using applications that can parse the .rsrc section allows an analyst to access and identify embedded DLLs, images, executables, etc of which may be used by the suspicious binary.

Linked Libraries and Functions

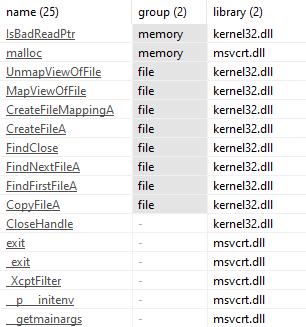

Identification of an executables linked libraries, either statically linked, at runtime or dynamically, provides a good understanding of the functionality of the malware. Shared libraries allow multiple programs to share common functions without the need for the functionality to be coded from scratch. Linked libraries are listed within the PE Header as Imports.

- Statically Linked Libraries: The least common method which involved importing the entire library into the programs own code.

- Runtime Library Linkage: Commonly used by malware, runtime linkage only loads the library when it is required. There are several Windows functions including ‘LoadLibrary’ and ‘GetProcAddress’ that allow any function in any library to be used which makes static analysis of these files difficult as the exact functions and imports are not listed.

- Dynamically Linked Libraries: These provide the best method of understanding what a programs functions are as the import libraries are loaded upon execution and often the exact functions called are listed within the PE Header. (The image to the left depicts an example, two libraries loaded with individual imports listed).

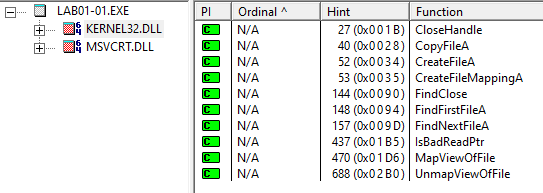

Exported Functions

Executables rarely export function by themselves, however if analyzing a suspicious DLL it is important to check the available exports. Exports are functions that can be called upon for use by an importing application. Normal software typically follows a standardized naming convention as displayed in the above Kernel32.dll functions, however malware authors can and do often attempt to mislead analysts by naming the functions incorrectly or in a meaningless manner.